In an era of all-out-give-‘em-hell war, it’s nice to think about the days of yore when armed disputes between nations were put in the hands of gentlemen—mostly “second sons”—who, after they had done their duty and covered themselves in glory, were eligible to marry gracious young women with titles like “Lady,” and set about raising a brood of children for the next generation. Well, maybe it didn’t happen that way exactly, but it’s nice at least to contemplate such legends.

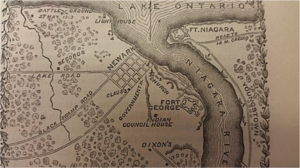

One of those legends involves the battle between the hurriedly-constructed Fort George located on the Canadian side of the Niagara River and Fort Niagara, a stone fortress begun by the French in 1687, captured by the British in 1759, and lost to the Americans in the treaty that ended the Revolutionary War.

Just across the river from Fort George stands the American stronghold known as Fort Niagara. Like their American counterparts, modern-day Canadians enjoy waterfront living. Once-vacant land between Fort George and the river is now clogged with apartments.

With its wooden buildings and earthen palisades, the hurriedly-constructed Fort George was no match for the stone-built Fort Niagara.

The story goes that British and American military officers had much more in common with each other than with the rabble whom they led. There was little to entertain gentlemen in the wilderness known as the Niagara Frontier, and in the early 1800’s, although diplomatic tension was building between their nations, they saw no reason to extend such unpleasantness to the personal level. Instead, the officers on both sides of the border frequently rowed across the river and entertained each other at elaborate dinners which featured everything including the traditional after-dinner toasts made with port wine before retiring to their own sides.

According to legend, during one such dinner at Fort George, a messenger brought word to the dining officers that the governments of their two nations had reached an impasse and their nations were officially at war. What to do?

Technically, of course, the Americans should be held has prisoners of war, but such action was unthinkable considering the circumstances in which the parties found themselves. The Americans might be allowed to depart immediately under a flag of truce, but that would mean leaving a sumptuous and perfectly edible meal not to mention drinkable wine on the table.

There was only one reasonable solution: both sides would ignore the message, finish their repast, toast one another’s countries over the last of the port wine and wish each other good fortune. Then the Americans would row back across the Niagara as they always had done in the past, and both sides would begin their war at a decent hour the following morning. The legend continues that for a number of weeks their “war” consisted of lobbing a few cannon balls at each other—carefully aimed to avoid any damage—before drilling the men on their respective parade grounds.

Peaceful (and costly) waterfront condominiums fill an area that was once wilderness patrolled by American troops on their side of the Niagara River.

According to Lt. Col. Ernest Cruikshank, in his book The Battle of Fort George, cannon balls were much too scarce and valuable to be wasted, and Lt. Col. Myers, the Assistant Quartermaster-General of Fort George, took pains to state in a report that the number of “round shot” picked up on the field exceeded the number fired from his guns on at least one occasion.

It’s a great story but, sad to say, at best it appears to be only partially true. On our visit to Fort George one of the docents confirmed the story of the mutual dinners, but he had never heard of the almost-interrupted one, and he said the story of the good-mannered exchange of cannon balls had to be a fable. In fact, once the War of 1812 got underway in earnest, it became as ferocious as any modern war. In May 1813, an early morning fog lifted to reveal American naval vessels off the shore of Lake Ontario, and a combined force under Colonel Winfield Scott and Captain Oliver Hazard Perry laid waste to Fort George and invaded the area. American troops occupied that portion of Canada for the next two years.

Winfield Scott eventually became a major general (at that time it was the highest rank in the United States Army) and served as general-in-chief until 1861 when age and ill health forced him to retire. Oliver Hazard Perry attained the rank of Commodore and became the “Hero of Lake Erie” when he led American forces in a decisive naval victory at the far end of that 241-mile long inland sea.

History honors the courageous men who perform such feats, but sometimes we do well to think of the unknown soldiers who served in the wilderness of places like the Niagara Frontier and relieved hours of boredom with proper dinner parties and polite artillery exchanges. Who knows? If only they had continued those tactics for a few years, the diplomats might well have settled the differences that brought about the conflict in the first place. Think of how much suffering could have been avoided and how much port wine would have been consumed! It’s a pleasant—and perhaps a noble—idea.

Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry as he appears today in Buffalo’s Front Park, facing the confluence of Lake Erie and the Niagara River.

Joe: Brings back many memories! Fort George was intended to protect western Lake Ontario and the entrance to the lower Niagara River. Fort Erie was intended to protect eastern Lake Erie and the entrance to the upper Niagara river. As a summer resident of Canada, when we were kids, we would walk to Fort Erie and play there all day almost every day. We all developed a love of history playing in the “Old Fort”