“No Person except a natural born Citizen … shall be eligible to the Office of President . . .”

Article II, Section 1, Constitution of the United States

Many amateur historians claim those words were added to the Constitution for the specific purpose of cutting out Alexander Hamilton who was not only born in a “foreign” country, but was not well liked by his peers because he was considered too much of a “monarchist.” We’ll straighten them out in a minute, but first let’s look at Hamilton the man.

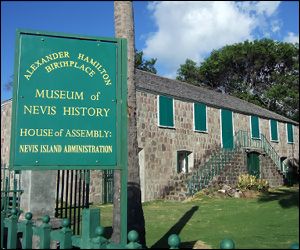

The Museum of Nevis History is built on the foundation of what is believed to be Hamilton’s birthplace

Alexander Hamilton was born out-of-wedlock on the Island of Nevis in either 1755 or 1757, and he lived there until about the age nine. The latest research shows that he also lived with his brother and both their parents on the nearby island of St Eustatius, which had a close relationship with the early United States and was the first to recognize American independence when the brig U.S.S.Andrew Doria received a 13-gun salute from the Dutch Fort Oranje–making it the first salute to an American-flagged warship in a foreign port.

Abandoned by their father, the family moved to St. Croix, USVI, where their mother she kept a small store until she died. Alexander was 13 at the time, and he and his brother James were now orphans. Alexander was taken in by a wealthy merchant, Thomas Stevens, went to work for him and by the time he was 16 was considered capable enough as a trader to be left in charge of Stevens’ firm for five months while Stevens was at sea. The leaders of the St. Croix community were so impressed by Alexander’s performance that they collected a fund to send him to the Colonies for an education.

Alexander made his way to New York City, where he entered King’s College (now known as Columbia) in 1773. He aligned himself with the Revolutionary cause and began writing essays for the New York Journal. Before he could graduate, the college was forced to close its doors because of the British occupation of the city. He and a number of other students joined a New York militia company called “Hearts of Oak.”

He led a successful raid that captured British cannons on New York’s Battery while under fire from a nearby warship, the HMS Asia. Soon after that he was promoted to the rank of captain, and he participated in the Battle of White Plains, the Battle of Trenton, and the Battle of Princeton before he was invited to take a place on George Washington’s staff.

He eventually rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and as served as Washington’s Chief of Staff. Although he admired and respected Washington, Hamilton longed for his command of his own, and he threatened to resign from the army if he didn’t get it. On July 31, Washington relented and gave him command of two New York regiments and two companies from Connecticut. He and his men participated in the Battle of Yorktown, where they took two Redoubts of the fort—one with bayonets in a nighttime action. As a result, they were present in October, 1781, when British General Charles Cornwallis, surrendered his army, and the war was effectively ended.

During the war, Hamilton continued a vigorous program of self-study, and he passed the New York Bar examination in July, 1782. In October of that year, he was accepted by the Bar and licensed to practice before the New York Supreme Court. When the finally British left New York in 1783, he often defended Tories and British subjects. In Rutgers v. Waddington, he successfully argued that a state statute should be set aside on the grounds that it violated the State constitution, which served as a “persuasive precedent” for the United States Supreme Court in the famous case of Marbury v. Madison.

As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton differed from many of his colleagues in that he supported a strong central government. He argued that the President should be elected for life, making the office an “elective monarchy.” Later, as the first Secretary of the Treasury, he created the United States Mint and the National Bank.

But his early training as a merchant trader had not left him. During the war, many of the soldiers were paid with promissory notes that dropped in value when the Constitution was being debated. These debts were bought up by wealthy speculators for pennies on the dollar, and, after the National government was formed, Hamilton argued the only legal course of action was to pay the speculators rather than the original holders of the IOU’s. His later support of a whiskey tax earned him even more enemies.

Hamilton’s New York home at the time of his death.

His political leanings eventually led to a clash with Vice President Aaron Burr, and in 1804, the two men fought a duel with pistols in New Jersey where dueling was not yet illegal. Hamilton was mortally wounded and after suffering for some 31 hours, died the next day. Depending on which date of birth you accepted, he was either 47 or 49 years old.

Now, as to that mistaken notion held by many amateur historians that began this story, Article II, section 1 of the Constitution was not inserted to exclude Hamilton from the presidency. In fact, the full text of the section reads, “No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution . . . shall be eligible to the Office of President . . .”

Clearly, Alexander Hamilton was a “citizen” of the United States at the time the Constitution was adopted. In fact, he was a New York lawyer and one of the delegates who signed that Constitution. Not only was he “eligible” to be President, today there are many historians who argue he would have made a darn good one.

Love these stories. Keep them coming…

Thanks.

Thanks for this great history lesson.

Thanks for this great history lesson!

Thanks for the research, it’s amazing how you take a slice of history and make it come alive .

Thank YOU for letting me know! Let’s get together soon!

Joe,

Almost as good as getting to see “Hamilton” on Broadway…. Keep up the fantastic work. Look make everyone look forward to seeing the next issue.