Family histories take many strange turns. Indeed, the words “E Purlibus Unum” seem to be most appropriate when we apply them to our own lives.

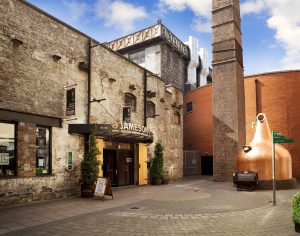

Irish distillers Pot Still Yard

In 1786, a Scottish lawyer by the name of John Jameson married Margaret Haig, whose brothers owned the Haig distilleries. John and Margaret had a son– who they named John of course. By and by, father and son took over the Haig venture and the John Jameson & Son company was formed.

John senior also had a younger son, Andrew Jameson, who set up his own distillery using the family name, and with his help the entire family business grew ever larger. In 1823, Andrew and his second wife, Margaret, acquired a new home in a place known as Daphne Castle in Wexford, Ireland. There the couple had five children, all daughters: Elizabeth, Helen, Janet, Isabella, and the youngest, Annie, who was born in 1840.

Annie was a comely Irish lass. She was born with a beautiful voice and a talent for singing. Early on, she developed a passion for opera and although her parents were not royalty in any sense of the word, they were, as the people of their town of Wexford said, “well fixed.” And so, when she became old enough to travel, they sent her to Italy to study her passion. In Italy, Annie met an older man, a widower, who was truly an aristocrat, and, unlike her family, he had a royal title to prove it. Giuseppe Marconi was swept away by the young woman’s talent–not to mention her Irish beauty–and he quickly proposed marriage which the Irish colleen accepted.

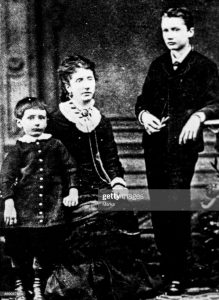

Guglielmo with his mother Annie Jameson and his older brother Alfonso.

The newlywed couple settled into a residence that was commensurate with their status in Italian society–the Villa Griffone, outside of Bologna, a seat of Italian culture. There the happy aristocrats had two sons who were named by their father according to an indisputable Italian tradition: the older one, Alphonso (Alphonse), was born in 1865, and the younger, Guglielmo (William), was born nine years later in 1874.

And there they lived happily ever after. Well, not quite. Although she loved Italy, Annie was determined that her children should be exposed to the Irish side of their heritage. When the younger son turned two years old, she moved with the boys to her hometown of Wexford, where she personally supervised their education for the next four years. The family returned to Italy when she was satisfied the boys were sufficiently grounded in Irish culture, and, although Bologna became their permanent home, she saw to it that they returned to Daphne Castle every summer.

Many people considered the younger son, Guglielmo, to be a genius, but he did not do well in school. Fortunately, his family was in a position to hire tutors, and he was “home schooled” in chemistry, mathematics, and physics at Villa Griffone. Even when the family traveled south to Tuscany or Florence to escape the chill of northern Italian winters, they were accompanied by special instructors, and later in life Guglielmo acknowledged the importance of Professor Vincenzo Rosa who taught him the basics of physical phenomena as well as new theories of electricity when he was 17 years old. The following year–again, thanks to his father’s influence–physicist Augusto Righi allowed him to attend lectures at the University of Bologna and even to use the University’s library and laboratory.

Many people considered the younger son, Guglielmo, to be a genius, but he did not do well in school. Fortunately, his family was in a position to hire tutors, and he was “home schooled” in chemistry, mathematics, and physics at Villa Griffone. Even when the family traveled south to Tuscany or Florence to escape the chill of northern Italian winters, they were accompanied by special instructors, and later in life Guglielmo acknowledged the importance of Professor Vincenzo Rosa who taught him the basics of physical phenomena as well as new theories of electricity when he was 17 years old. The following year–again, thanks to his father’s influence–physicist Augusto Righi allowed him to attend lectures at the University of Bologna and even to use the University’s library and laboratory.

Villa Griffone outside of Bologna, Italy where Guglielmo and his servant Mignani performed experiments.

It was Righi who sparked Guglielmo’s interest in radio waves, and the young genius built much of his own equipment in the attic of the family home, Villa Griffone, assisted by his personal butler, a man named Mignani. He continued his work even when the family summered at Daphne Castle, where some of the male servants were assigned to help him by stringing wires and sending them aloft in kites while he continued his experiments. It turned out that sending those wires airborne was very important, because from them he learned that as they increased the height of a vertical, monopole antenna, he was able to transmit radio waves at far greater distances.

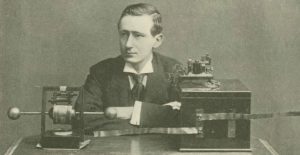

The young man who changed with world with wireless tecnology.

By 1901, the young 27-year old Italian-Irishman who had grown up in two cultures, was ready to demonstrate his invention by transmitting a radio signal across the Atlantic, from London, through equipment he had set up at stations in Cornwall, England, and in Clifden, County Galway, Ireland, to Nova Scotia–equipment and stations that were bought and paid for thanks to the wealth of his father, Giuseppe, and his mother, Annie Jameson.

So the next time you’re in the mood for “a wee dram,” make it a Jameson’s Irish Whiskey, and raise it in a toast to the heiress of the Jameson clan, and to her husband the Italian aristocrat, and to their brilliant son, Guglielmo Marconi, who invented wireless transmission.

Well done. Enjoyable reading.

as smooth as ever; and just the right neat click!

A great read. Drew me right in.

Thanks Joe.